If we have the appropriate architecture, technology and methods, why not take advantage in new research of what others have delivered to the science of knowledge?

02|OCTOBER|2023

Gabriel Rada: Let's talk about sustainable knowledge

If we have the appropriate architecture, technology and methods, why not take advantage in new research of what others have delivered to the science of knowledge?

In the world of knowledge, the pandemic came to give us a jolt that, when seen in perspective, was just and necessary. Although it has been one of the most fruitful periods in history in terms of information production, with almost 1 million articles published to date, over time we realized that what was published quickly became outdated to be replaced by new knowledge.

As a result, people received changing and divergent messages, which in turn were a reflection of the critical moment we were living through and of the complexity that working with evidence usually implies.

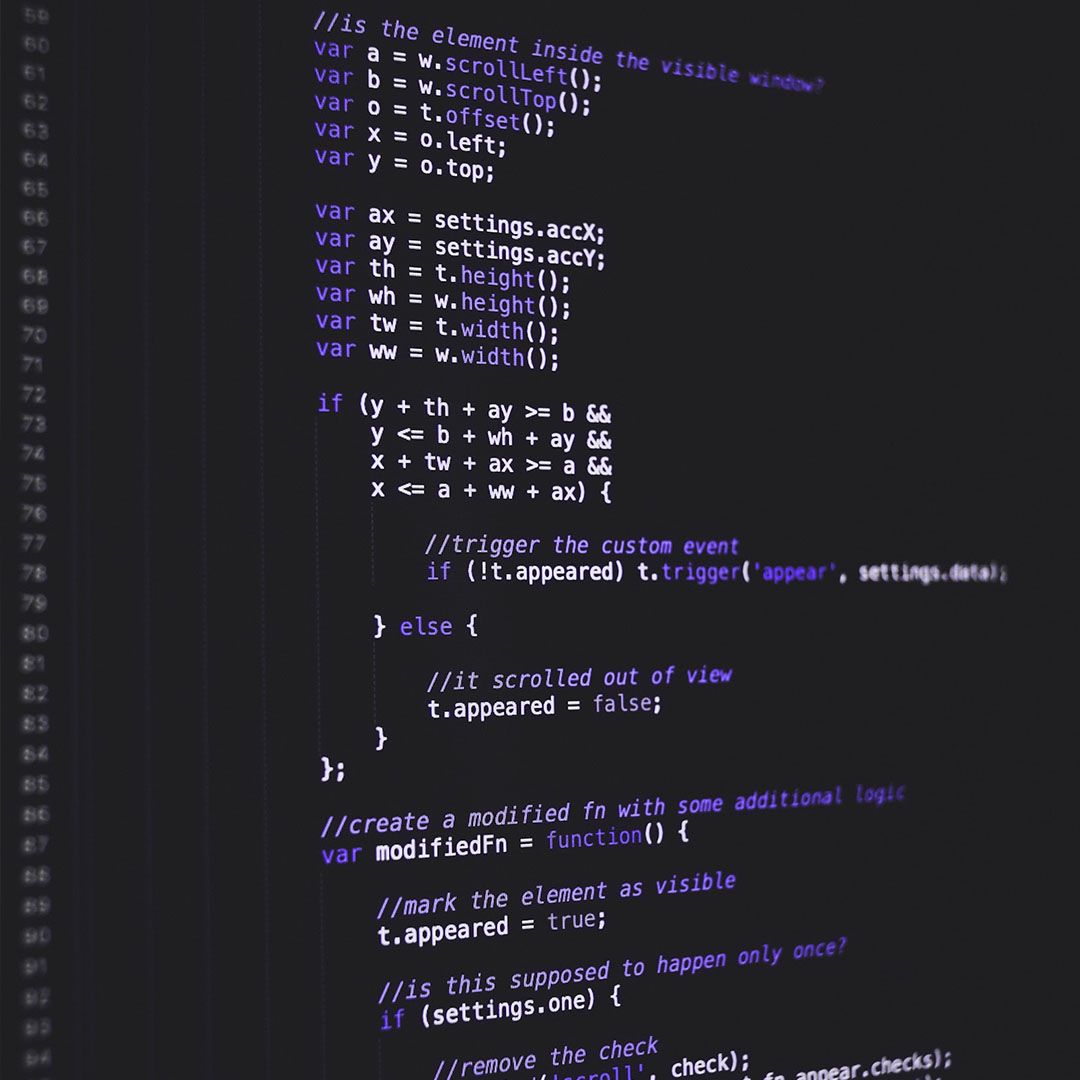

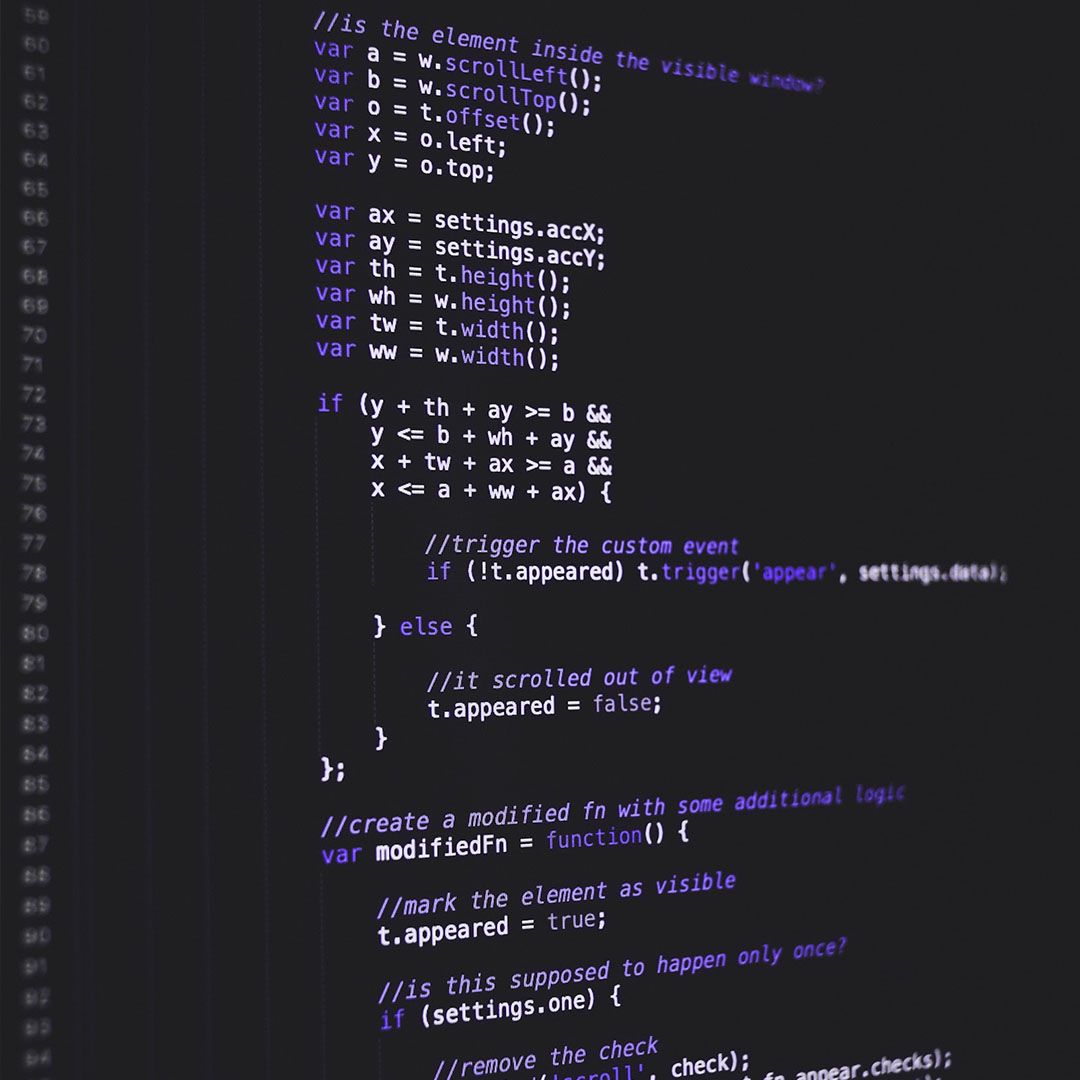

In order to counteract the rapid obsolescence of evidence/information and seek ways to keep the information up to date, different formats have been created. Some are living models, which -with infrastructure and technology- incorporate the evidence as it is produced. Thus, we speak of living evidence as a way of synthesizing and keeping up to date, with the assistance of technological tools, the enormous amount of information that is constantly being produced.

However, although it has been a good way of summarizing large volumes of data, there is a problem that persists and that has to do with the fact that, in general, when doing research, scientists tend to restart the process of exploration and analysis, and do not rely on the latest existing knowledge in the field.

For example, if one wants to determine the effectiveness of aspirin in the treatment of heart attacks, the methodology involves revisiting everything that exists, rather than starting from the latest findings. And while everyone is trying to do it as quickly as possible, with artificial intelligence, in a way, you could say that they are 'starting from scratch'.

If we have the appropriate architecture, technology and methods, why not take advantage of what others have delivered to the science of knowledge in new research? It is something like standing on the shoulders of our predecessors, reusing their discoveries to start from a base point and thus adding more bricks to the building of knowledge.

This idea of starting from scratch has been deployed because the knowledge production system is very misaligned with the objectives it should have and responds, rather, to demands imposed by the market and what is asked of researchers and universities. Incentives today have to do with the idea of publishing a lot and constantly, but as information has increased and problems have become more complex, few people or groups have dared to tackle unmanageable questions and challenges, which -incidentally- require more work time to reach successful results. In addition, there is little incentive for collaboration. And although during the pandemic some attempts were made along these lines, it was difficult to maintain them after a short period of time.

At Epistemonikos, through our Sustainable Knowledge Platform or SK Platform, which brings together about 20 evidence synthesis tools, we are promoting a new concept: sustainable knowledge, which refers to the reuse of data in research work.

Although the word sustainability is not used much in health, this concept is far from being an element associated with something purely environmental, but has to do with how we ensure that projects such as this one are not an isolated initiative. That is to say, that it is something that can be maintained over time and that can be scaled up.

Because what has happened is that while the amount of data is increasing exponentially, the knowledge curve has flattened. There are even voices that say that it has decreased. This is currently happening in many areas: we see that researchers who are in the trenches are overloaded with information and cannot cope with it, and finally they return to the original model, which is to stick to what they learned at the university.

The heart behind our proposal and the technologies we are developing combines two fundamental elements: artificial intelligence and collective human intelligence. Both elements appeal to the collaboration that, through technology and reasoning, give the possibility of generating a system where large volumes of knowledge are gathered to deliver synthesized, updated and fast answers, and above all, that account for all the existing information on certain topics.

Gabriel Rada is an internist, co-founder, president, and CEO of the Epistemonikos Foundation. He is an associate professor at the Faculty of Medicine of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.